WITHIN A YEAR, COKAL EXPECTS TO BEGIN PRODUCING COKING COAL FROM THE CENTRAL KALIMANTAN REGION

By John Miller, Australian-based editor

| Cokal’s chief geologist Yoga Suryanegara (left) and other team members examine core from the BBM drilling program. |

Cokal Ltd. is well advanced on the road to production at the Bumi Barito Mineral (BBM) coking coal project in central Kalimantan, Indonesia. The company expects production to begin in the first half of 2015 at an initial annual rate of 375,000 metric tons per year (mtpy), and ramping up after about six months to the full designated capacity of 2 million mtpy.

The only hurdle to overcome in late May before beginning the nine-month construction phase was securing the production forestry permit for which Cokal expected final approval within weeks.

A definitive feasibility study (DFS) has confirmed that the BBM mine, associated facilities and transport systems can be developed as a low capital cost operation with moderate- to mid-range operating costs. BBM is northwest of Puruk Cahu, the capital of Murung Raya Regency.

The study approached the development as a 2-million-mtpy, open-cut mining operation and identified that BBM’s relatively low-ash, low-sulfur, low-phosphorus coking coal would command a high value as blending feed in the premium coking coal market. The formal risk analysis identified no issues that could not be managed by reasonable controls that would prevent effective construction and operations.

The total estimated development capital required to deliver the production rate, including developing a coal handling preparation plant, haulage road, and all necessary transport and site infrastructure is $75 million, assuming that mining, barging and hauling equipment will be provided by the respective contractors.

A recently released JORC 2012-compliant estimate for the eastern portion of BBM shows a 261-million-mt resource, comprising 10.5 million mt measured, 13.5 million mt indicated and 237 million mt inferred. Further infill drilling is likely to define additional resources and increase measured and indicated resources.

“I am absolutely pleased with the DFS and its outcomes,” said Cokal Chairman and CEO Peter Lynch. “We did a pre-feasibility study (PFS) in October 2012 and then went into the detailed definitive study, enabling us to get within plus or minus 10% of operating and capital costs. We also refined the capital project schedule in a bid to make the capital more efficient. The DFS shows an even lower upfront capital cost, so we have decided to delay a little of the capital spend so we can get into cashflow sooner and then fund enhancements in the following 12-18 months after production begins.

“The DFS reinforced our view on operating and capital costs, backed up, particularly with larger items, by actual quotations from contractors and suppliers.”

Final Steps

Lynch said all permitting has been secured except the final step, the production forestry permit. “We commenced the application for this in February 2013 and it is with the minister. There were some minor issues, including changing coordinates on the survey plan. In Indonesia, there are regency, provincial and national government levels, and there can be a lot of ‘too-ing and fro-ing’ between departments.

“Once we have the permit, we have essentially jumped all major hurdles, having already secured the production mining licence. After receiving the final permit, we have to peg the outline of the permit using square concrete posts,” Lynch said.

In regards to financing, Lynch said Cokal has been in discussions with a number of parties for a long time. “After receiving the PFS, we started a ‘closed expressions of interest’ process involving companies we knew and trusted — steel mills, trading houses, finance sources — many of whom had approached us directly. We didn’t just open the gates and ask ‘is anyone interested’ — we targeted those familiar with the project. Now we have the DFS and these contacts are rechecking their numbers using the definitive information to come up with final funding positions. Attainment of the production forestry permit is like a condition precedent they need to see satisfied before committing.

“We have now chosen to accept a $150 million debt funding proposal from Platinum Partners, which provides an initial $80 million to $100 million to cover the initial capital cost of the BBM project to a design capacity of 2 million mt. Further drawdowns are accessible as project delivery performance is demonstrated.

“If construction starts in June or July, we can essentially put first coal down the river late in the first quarter or early in the second quarter of 2015. The production profile for the first six months sees us budgeting to produce 375,000 mt of product coal, allowing for a soft ramp-up. After that, we expect to be operating at full annual capacity,” Lynch said.

|

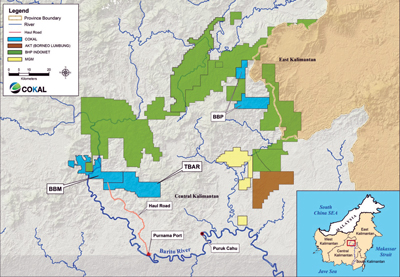

| The BBM permit area adjoins the Barito River in central Kalimantan with Cokal’s next project, TBAR, adjoining to the east. |

Beyond BBM

Cokal has backed off at its other Indonesian projects to focus on BBM. Once it is funded and in production, the next priority will be the adjoining Tambang Benua Alam Raya (TBAR) project. “We are obtaining the exploration forestry permit, which will enable us to use high-capacity drill rigs to prove up a resource,” Lynch said. “It is the next priority because if we find resources of sufficient quality and quantity, we will be able to increase annual production at BBM or extend mine life with the potential to give us greater return on the BBM infrastructure investment. Most BBM capital will be invested in the haul road, barge loading jetty, the joint venture company we are forming for a specialized barging system and the intermediate stockpile. The more coal we can put through that capital, the better off we are.”

Beyond that, he said, it is about focusing on a largely undeveloped coking coal basin. “The North Barito Basin has about 10 billion mt of resources, compared to Queensland’s Bowen Basin with 35 billion mt. It is highly sought-after coal that is complementary to some of the new coking coals from Australia and Mozambique. New coal from the developing Rangles formation of Central Queensland has lower vitrinite and higher phosphorus levels than coal previously mined in the Bowen Basin, while coal from Mozambique has high ash and a bit of phosphorus. North Barito Basin coal has very high vitrinite, almost no phosphorus and low sulphur, making it ideal for blending.

“The basin only has two operating mines — Borneo Lumbung at an annual capacity of 3.5 million mtpy and MGM at 1.5 million mtpy but expanding to 2.5 million mtpy — and is like the Bowen Basin was in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

“We have been doing a lot of work to determine what the most promising parts of available projects are and how they complement what we are doing. Our focus is on the western side of the basin where we have four projects, including AAK and AAM. Our aim is to build a solid base where we have the potential to grow in the next 10 years to get to 10 million mt of annual production.”

|

| An outcrop of bright coking coal at Cokal’s BBM project, which is characterized by thick seams. |

Working Together

Lynch explained that it is a tough environment to bring a project to the market with sentiment for coking coal at all-time lows and volatile prices, while the political cycle in Indonesia is unpredictable owing to a presidential election later this year.

“The current regime has been criticized for not doing much, but they have made inroads into tackling corruption and have consolidated the country by getting everyone working together and moving forward, albeit slowly.

“I believe this has set the scene for significant growth following the presidential election. After all, Indonesia has the world’s fourth biggest population, a 5-6% growth rate, is resource rich, has a highly educated and young demographic, and everyone wants to get ahead, resulting in a lot of aspirational activity. There is a lot of foreign investment interest, but many are holding off and waiting for the election. Once this is over, and I think there will be a positive result, investment will start pouring in.

“Where we sit, if we can get into production now, we will be at the start of the growth wave. When Indonesia starts to become the flavor of the month, every man and his dog will be there, so we have an early mover advantage.

“There’s a positive feel amongst the people, and Indonesia has a bright future. To me it’s a safer place to do business than Australia, the people want to learn so they can do better and the labor cost is incredibly cheap. In provincial areas, the labor rate is about half that of inland China. Indonesia also has a competitive cost structure. As the economy picks up, costs will increase, but there is still a significant buffer to the Chinese structure.

“Indonesians are all about pride, they love getting a chance to have a go, and smaller companies like Cokal offer quality opportunities for them to play a significant role in the company’s development. They like having the autonomy we offer and want to see Cokal do better. They set out each day to prove that you have done the right thing by employing them,” Lynch said.

|

| Cokal Chairman Peter Lynch in front of an outcrop of coking coal at the BBM project. Cokal expects production at BBM to start in early 2015. |

Indonesian Growth

“Many people talk about growth in China and India but forget about Indonesia. The worst ones doing this are Australians, despite Indonesia being so close and Australia being well positioned to capitalize on growth there as the two societies are complementary,” Lynch said.

“Australia has a lot of wealth, a small population, expertise and has been through what Indonesia is experiencing now about 35 years ago. Indonesia is struggling with things like resource nationalism and downstream processing, which is what Australia went through in the 1970s. The two countries should be sharing that experience and Australia’s manufacturers should consider moving to Indonesia where they have a better chance of surviving. Australia could then have a strong parts industry supplying Indonesia’s manufacturing,” he said.

|

| The proposed transport system along the Barito River for coking coal from BBM. |

Self-empowerment

“In central Kalimantan there is not a strong mining history, unlike east Kalimantan, and Cokal decided to get involved in significant corporate social responsibility (CSR) early on,” Lynch said. “Because everything is relatively inexpensive, it doesn’t cost much for mining companies, but it can have a huge impact depending on how it is done.

“Cokal has helped set up a junior high school. There is a population of about 12,000 within 60 km of our site, and previously the kids would get to sixth grade but then leave school as it was too far to the junior high school — about three hours down the river and the same up the river at the end of the day. We sat down with the communities, asking them what would make a difference, and the first answer was always education.

“Rather than just becoming the funding beneficiary, we said if you provide the labor, we’ll pay for materials. The entire community got involved and built a junior high school in a matter of months while we paid for the wood, concrete, paint and other materials. They are proud of it because it’s theirs, and we helped them achieve it.

“There was also a need for teachers, and we didn’t want to become an employer of teachers, so we negotiated a bursary system with the provincial government. We essentially provide a bursary so the government can employ four additional teachers who are part of the provincial education system. We have committed to this for four years and hope by then we’ll have the budget mechanism to ensure it is ongoing. We are trying to help, not just by adopting a hand-out mentality but by self-empowering them.

“We also helped locals set up a cooperative, which supplies the food, meals, fuel and other supplies we need. It also helps with small building projects and provision of temporary camps around the site. They are essentially acting like a contractor — it’s their own business, they are paying taxes to the government and employ local people. It is a similar self-empowerment model to that established by Medusa Mining in the Philippines. It is not just about mining education, but also agriculture, which helps get better productivity from crops. In this way they don’t just rely on the mining project, it extends into betterment of the ongoing existing economy,” Lynch said.

|

| Barging is the preferred method of transport from the BBM project. |

Indonesian Advantages

Compared to Australia’s timeline for bringing mining projects online, it has been a relatively short road toward production for Cokal. Lynch said in the last 10 years Australia has gone backward in this regard. “It was possible to get projects into production in two or three years, but now it is a five- to 10-year slog. In Indonesia, the system is bureaucratic because of the levels of government in various stages of autonomy, but overall there is a strong desire to move forward and make things happen. Despite the bureaucracy, the underlying drive has ensured that the approvals system is of an international standard, including AMDAL for environmental approvals.

“At least you know what you are dealing with, whereas in Australia there is supposedly a system, but it is subjective and politically tarnished. Whenever a new project comes up, as soon as a group becomes vocal with their concerns, the company, which has often done a detailed technical review identifying all issues, is often forced to go into a time-consuming and costly supplementary process because local politicians don’t want to face up to some perception of negative sentiment.

“It hasn’t always been easy in Indonesia owing to the bureaucracy with one level of government thinking the process works differently to what another level of government believes. Despite this, there’s ultimately a way through. Cokal has been aided by establishing a successful Indonesian team. We use some consultants but have a very strong team that fully understands the process. We even have government using us as an example to others. Our BBM process for the AMDAL and mining approvals is used as a model for the province to progress further projects,” he said.

|

| Cokal Indonesia President Director Garry Kielenstyn awards university scholarships in Murung Raya Regency as part of the company’s CSR program. |

Risk Reward Investment

Lynch said as an investment destination, Indonesia is perceived as being high risk, but it is risk that is rewarded: the geological potential of Indonesia is largely untapped, which means juniors operating in Australia have to contend with more marginal projects; in terms of approvals, it is quicker in Indonesia; labor rates are at least a 10th of the cost of Australia; and there is half the shipping distance to the main markets of China, Korea, Japan and India. “The significant differences between most Indonesian and Australian coal projects are that infrastructure costs are a lot less and transport approvals much simpler, particularly for projects serviced by a river. We don’t need to form a complicated consortium to negotiate further capacity on rail lines or ports, which are often controlled by a major. The cost to get the coal to an ocean-going vessel is much less, at about $2.54/mt for Cokal, and we don’t have to put capital into that process apart from the barging fleet. All we have to do is sign a contract with the floating crane operators to load from barges to vessels. This compares to costs of up to $13/mt to get Australian coal to vessels. As well as being much cheaper, easier and quicker, you don’t have the interrelationship hassles often seen in rail and port deals.

“We have good faith in Indonesia despite many people saying bad things. We don’t listen to the chit-chat; we’re having a go and believe we’ll be rewarded because we have a good company setup, giving us respect from the country, which will ultimately lead to positive project outcomes,” he said.